The period between 1905 and 1914 saw the introduction into the motor industry of many names which have since become famous, and of many inventions which have contributed to the efficiency of the modern motor car

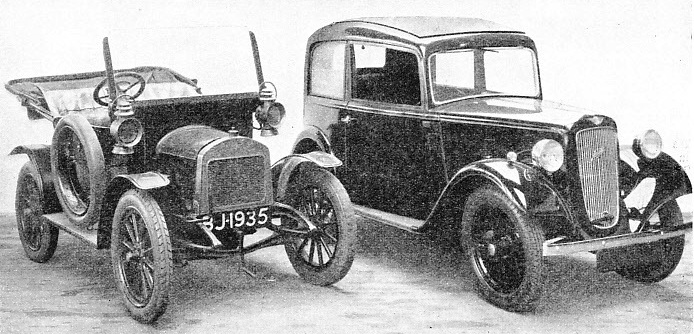

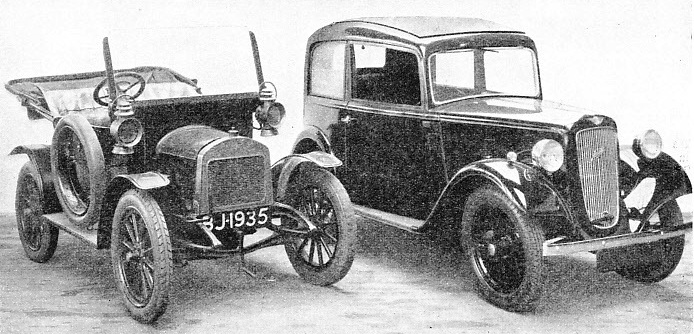

TWO AUSTIN SEVENS —the first single-cylinder 7 horse-power car produced in 1910 and the familiar 1937 four-cylinder saloon. The prototype of the four-cylinder model did not appear until 1922, but the 1910 model won fame as a light and economical car.

THE ten years that preceded the war of 1914-18 were a period of intensive development for the motor car. But for the outbreak of hostilities there is little doubt that the mechanical and artistic excellence of the modern car would have been attained some years earlier.

In the chapter “Early Car Designs of the Twentieth Century” development in the early nineteen-hundreds was described, and the formation of many famous motor manufacturing companies was noted. In the following years many more companies were formed, and many of them are still in the forefront of the industry. A car which, under the guiding hands of the late Sir Henry Segrave, Sir Malcolm Campbell and many other famous drivers, was destined to make motoring history was the Sunbeam. The first Sunbeam car was produced by John Marston, Ltd, of Wolverhampton, as long ago as 1899. This was a 6 horse-power single-cylinder car. A 2¾ horse-power three-wheeler, with the engine mounted over the front wheel, was produced later. In the space of a few months, however, the little three-wheeled Sunbeam-Mabley gave place to the six-cylinder Sunbeam of 1904. This greatly improved model was fitted with driving chains running in oil baths, similar to those used on the Sunbeam pedal cycles. The car was fitted also with a dynamo for charging the accumulators. Sunbeams quickly came to the fore in the world of racing, and in 1912 a team of Sunbeam cars won the two-days Grand Prix de Regularite held in the north of France. The distance of 957 miles was covered at a speed of over 60 miles an hour.

Reference has been made in the chapter “Early Car Designs of the Twentieth Century” to the Wolseley car designed by Mr. Herbert Austin (now Lord Austin). At the age of eighteen, Herbert Austin emigrated to Australia, where he became manager of the Wolseley Sheep Shearing Company. He returned to England in 1893 to supervise the manufacture of sheep shearing plant and, on his own admission, turned his mind to mechanized road transport because of the labour of propelling a pedal cycle to and from his work in Birmingham. The Wolseley car was his first effort in this direction. A car designed by Herbert Austin was exhibited at the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1896, and in 1900 his 3 horsepower two-seater carriage won a silver medal for its performance on a 1,000 miles trial. In 1905 Herbert Austin founded his own company with a small factory at Longbridge, seven miles from Birmingham. The original Longbridge factory covered 2½ acres, and had a capacity of 120 cars a year with a staff of 270 people. The first Austin car, produced early in 1906, was a 25-30 horse-power four-cylinder tourer whose appearance even to-day would be regarded as reasonably conventional. By 1910 the factory had an area of 8 acres, and the 1,190 Austin employees produced 576 cars. In that year the first “Austin Seven” was built, but this pioneer light car differed considerably from the world-famous “Seven” evolved in 1922. The original “Austin Seven” had a single-cylinder engine of 4⅛ in. bore by 5 in. stroke. By 1914 the personnel of the Austin works had risen to 2,000, with an output of 1,500 cars a year.

A car which has retained its main characteristics, but has been greatly improved in detail, is the well-known Jowett, first produced at Bradford in 1906. The engine was of the two-cylinder horizontally-opposed type, and the soundness of the design may be gauged from the fact that for over thirty years the two-cylinder power unit served the Jowett exclusively. Exceptional economy and good “pulling” power were the chief characteristics of the two-cylinder model. The introduction of a four-cylinder Jowett made no difference to the opposed horizontal arrangement of the engine.

The present Armstrong-Siddeley firm also originated in 1906. Under the title of the Deasy Motor Car Manufacturing Company, the firm (now amalgamated with Armstrong Whitworth) was founded by Captain Henry Deasy, and in 1909 the company was joined by John Siddeley (now Lord Kenilworth). The Siddeley-Deasy cars were steadily developed until the war, when the company’s activities were turned to aircraft production.

The year 1907 saw the formation of the Hillman firm by the late William Hillman. The first Hillman car, designed by Louis Coatalen, was entered for the 1908 Tourist Trophy Race, in which it covered the fastest lap. The Hillman factory was established at Coventry and the cars produced there for the first few years were of the 25 horse-power type. In 1912 the Hillman Company produced a successful 9 horsepower car for the light car trade.

It was in 1907 also that the Rolls-Royce Company, founded in 1904, held a remarkable 15,000-miles reliability road trial with the “Silver Ghost”, a 40-50 horse-power Rolls-Royce with a six-cylinder engine. The trial was officially observed by the R.A.C. The car ran for 14,371 miles without any signs of breakdown other than tyre troubles, and these no doubt were occasioned by the roads of that period.

14,371 Miles; Repairs £2

Despite the bad roads, however, the “Silver Ghost” exhibited little wear after its astonishing run, on the conclusion of which the whole car was dismantled and examined. Any part showing the slightest sign of wear was replaced, but the repair bill came to only a little over forty shillings.

The “Silver Ghost” chassis has been modelled to a scale of three inches to the foot, and the model is preserved in the Science Museum at South Kensington, London. The design provides an interesting illustration of British motorcar practice of the 1907 period. The original car had a six-cylinder engine of 4½-in. bore and stroke, developing 48 horse-power at 1,200 revolutions a minute. The cylinder blocks were cast in two groups of three, and the valves were arranged at one side and operated by a single camshaft. The hollow crankshaft was provided with a bearing between every two adjacent cranks and lubrication was carried out by oil under pressure. The lower half of the aluminium crankcase was removable for inspection. The carburettor was adjustable from the dashboard and the speed of the engine was controlled by a centrifugal governor acting on the throttle.

The ignition system was of special interest, as the plugs were fitted to each cylinder in duplicate. One set of plugs was operated by an accumulator and coil, the other set by a magneto.

Unsurpassed in the excellence of its design and construction, the Rolls-Royce “Silver Ghost”, as all examples of the type came to be called, held pride of place in the world of motoring until even better models were evolved by the same company.

From the motorist’s point of view, perhaps the most important feature, even of the earliest Rolls-Royce cars, was their silence in running. Most cars of this early period were extremely noisy and many attempts were made to achieve some degree of silence. This fact accounted for the popularity of the electric brougham in the pioneer days of motoring, although, judged by modern standards, such vehicles would be considered noisy to-day. The introduction of a powerful car with a silent internal combustion engine was hailed with delight.

The famous Model T chassis on which, in 1909, the Ford Company had decided to concentrate, was so built that it could carry a saloon, tourer, coupe or landaulette body as required. The great point about this decision was that the most expensive part of the motor car could be produced in vast quantities at a reasonable price. Henry Ford had decided that it was sound policy to sell thousands of cars annually at low prices. In Britain firms such as Rolls-Royce decided to sell a few cars of super excellent workmanship to those who could afford the cost of such superiority. Both manufacturers were proved to be right: prospective buyers are not confined to one end of the financial scale. Markets were found as readily among the people of modest means as among the rich.

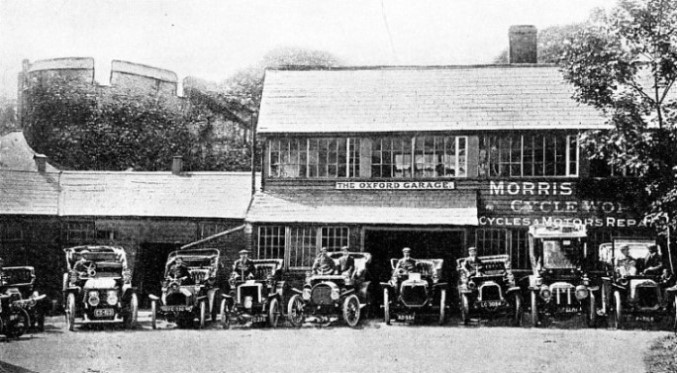

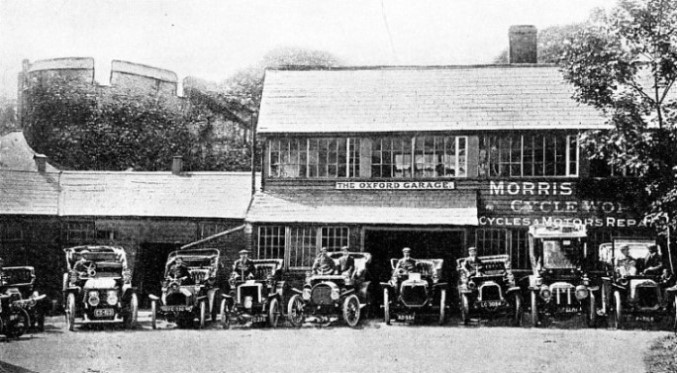

BIRTHPLACE OF THE MORRIS CAR. The original Morris Cycle Works in Long Wall, Oxford, from which the vast Morris organization of to-day has been developed. Even in the early days, as the above illustration shows, these small works were a rendezvous for motorists and their cars. Among the makes of car illustrated are Wolseley, de Dion, Humber and Panhard.

In many ways Henry Ford’s task, to supply the waiting thousands with cars, was the heavier. The 1908-09 sales of over 10,000 cars convinced Ford that even his big modern factory at Piquette Street, Detroit, was inadequate. He bought sixty acres of land at Highland Park, some distance out in the country from Detroit, and planned the biggest factory the world had ever seen. The Highland Park factory was built and extensive experiments were carried out to ascertain the best methods of car construction and assembly. Henry Ford paid high wages, and throughout his workshops he eliminated all waste, whether of time, of floor-space or of energy. His idea was to place machines and. men so that the components should travel the shortest possible distance in the finishing process. Then, by the use of conveyers, the job would be brought to the workmen for final assembly.

The first moving assembly line, now an essential of quantity production, was tried in the Ford works in April 1913, and the idea is said to have originated from the overhead trolley system used by the Chicago packers for the dressing of beef. The first experiments were carried out on the assembly of the flywheel and magneto components. By allocating twenty-nine operations to the task, with a man to each operation, the assembly time was cut, after much study and experiment, from twenty minutes to five.

Sleeve-Valve Engines

The assembly of the engine was the work of eighty-four operators, and a threefold improvement in assembly time was achieved. The plan was next tried on chassis assembly, with a reduction of time from twelve hours twenty minutes to one hour thirty-three minutes.

After the operations of the Ford Motor Company in England in 1909, a British company was formed in 1911 for the manufacture of Ford Cars at an immense factory at Trafford Park, Manchester.

The year 1909, apart from the beginning of the Ford Company’s activities in England, was a period of considerable importance in the story of British motoring. The opening of Brooklands racing track in Surrey provided an excellent opportunity for car trials and the setting up of records.

One of the outstanding British cars of the year was the Sheffield-Simplex, a five-seater equipped with screen and hood. A remarkable feature of the car was the absence of the customary gear box. Here was yet another attempt to provide “silent” running — this time by the use of a direct drive without gears. At the same time the design of the Sheffield-Simplex satisfied the craze then existing for all-top-gear driving.

The Rover Company announced a 6 horse-power car in 1909, with the engine and gearbox built in one unit. A quadrant gear lever was fitted, and the controls, were mounted on the steering column. At the same time the Sunbeam Company brought out a

14- 18 horse-power car designed by Coatalen. The Daimler firm introduced a 15 horse-power car driven by the smallest make of Knight sleeve-valve engine, with final drive by worm wheel. This was yet another contribution to the solution of the noise problem.

Two Mercedes cars of this period are worthy of special attention. One was a 15-20 horse-power car with a 4-cylinder engine, leather-faced cone clutch and shaft drive. A later Mercedes was a 6-cylinder, 75 horse-power car fitted with a “torpedo” body that even to-day would be classed as modern, although perhaps not conforming to the highest standards of streamlining.

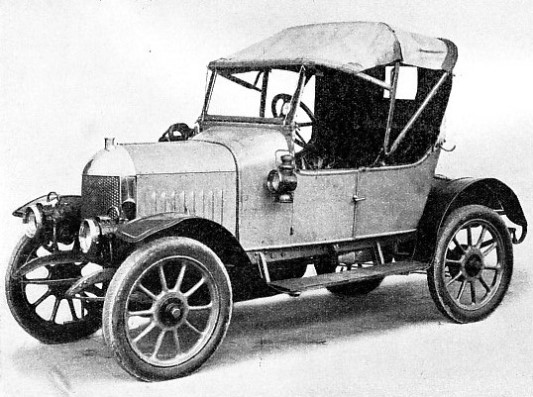

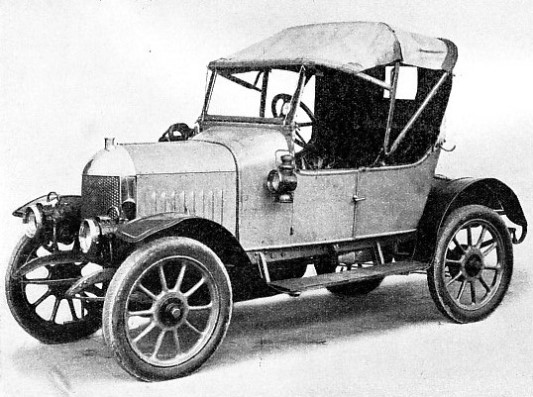

THE FIRST MORRIS CAR — an 8-horse-power Morris-Oxford produced in 1912. The resemblance to the famous Morris-Cowieys is apparent, although these cars were not built in large quantities until 1919. This early car was built in the Oxford garage illustrated above.

Complete touring cars sometimes cost only some £20 more than the bare chassis, from which it may be inferred that coachwork was rather less elaborate than it is to-day, when bodies may cost between £250 and £1,000 on expensive chassis. The saloon, as we know it to-day, was a rarity; the most expensive were priced at about £250. William R. Morris (now Lord Nuffield) built the first Morris car in 1912 at a small factory in Long Wall, Oxford. The little workshop at Long Wall was styled The Oxford Garage, and here the enormous Morris Motor business was started by Lord Nuffield as a bicycle shop. Morris cars were not, however, produced in large quantities, until after the war of 1914-18.

A British car that has established for itself a fine reputation in road races and on the track is the Riley. William Riley, the founder of the Riley Company, was originally in business as a weaver in Coventry. From weaving, however, Mr. Riley turned to bicycle manufacture in 1890. Pedal cycles gave place to motor cycles, and in 1898 the first Riley car made its appearance. Every part of the car was made in the workshops of the Riley Cycle Company. All types of motor cycles, quadricycles and three-wheelers were then made by the company and in 1905 there appeared the first example of a famous model — the 9 horse-power Riley light car. The engine was a V-twin with the cylinders set at an angle of 90 degrees.

In 1913 two cars of outstanding merit were produced, although most manufacturers had by this date achieved wonderful results in car design and performance. One of these cars was the 45-50 horse-power Mercedes, capable of remarkable acceleration, and the other was the 30-98 Vauxhall, a model so far ahead of its time that many of these cars are still running.

The year 1913 saw also the production of the first four-cylinder A.C. car, of which the later 6-cylinder model was destined to achieve fame under the guiding influence of the motoring pioneer Selwyn F. Edge.

During the decade preceding the war of 1914-18 the comfort and convenience of motoring received considerable attention. Few of the real ancients among automobiles, for instance, were provided with any sort of protection from the weather, but by 1905 the use of a folding hood was coming into use. Hoods were supplemented by side screens of canvas with mica panels, and by 1910 the use of a windscreen was almost universal. Before the advent of the “scuttle dashboard” — see accompanying illustration — the windscreen was placed too far ahead for comfort.

First Detachable Wheel

By the time the car engine had attained to a state of reliability that rendered night driving reasonably free from breakdown, the problem of lighting was tackled. The candle lamp, last remnant of the “horsed” carriage, gave place to paraffin side lamps and the necessity for a good headlamp was overcome by the use of acetylene gas. Headlamps using acetylene, supplied by separate generators carried on the car, attained a high standard of efficiency and were in common use until the all-conquering electric lighting made its appearance shortly before the war.

Reference has been made to the tyre troubles that seemed to be inseparable from pre-war roads. Many ingenious devices were evolved to combat the toil and trouble occasioned by burst and punctured tyres; but the problem was tackled from the wrong end. Motor traffic had not, at that time, exercised any influence on the improvement of the roads. Many types of “spare rims” which, complete with ready-inflated tyre, could be attached to the punctured wheel, were patented in the period from 1904 to 1911. Moreover the modern method of using a complete wheel was introduced during this period. As early as 1905-06 a detachable wire wheel was patented, and this, apart from its convenience in time of tyre failure, was a great improvement on the more common type of wheel with wooden spokes. Another pre-war innovation was the pressed steel wheel, also detachable, which was patented in 1908 and 1910. This type of wheel consisted of two pieces, each pressed out of a circular plate. The spokes were formed during the pressing operation and the edges of the disks were bent to form a rim for the tyre. The two portions of the wheel were then welded together at the edges, a hollow steel boss having been inserted between the disks.

With nearly all the manufacturers engaged in the production of munitions and aircraft, the development of the motor car was at a standstill during the period 1914-18. At the end of the war, however, the motor industry, despite the inevitable slump, made rapid strides.

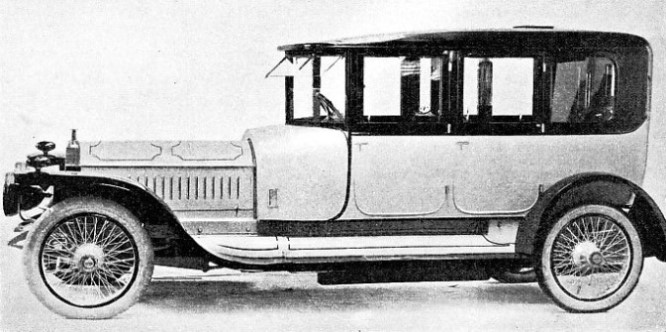

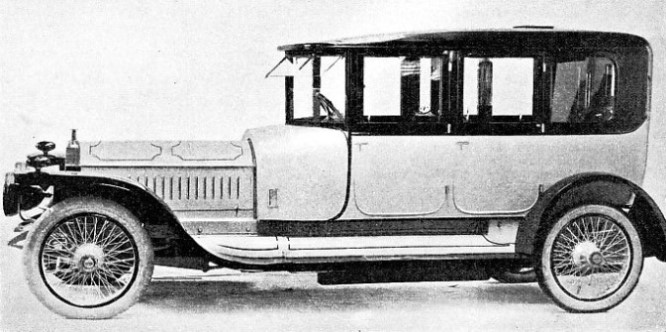

LUXURY CAR OF 1912 — a 38 horse-power Napier of advanced design. Saloon bodies were rare at that time, but, apart from the low level of bonnet and radiator, this car had lines that would scarcely appear out of place to-day. The “scuttle dashboard” may be noted.