© Wonders of World Engineering 2014-

The story of steam coaches which were tried before railways were developed is romantic and important. It was in road transport that the earliest experiments in the propulsion of carriages by steam power first showed signs of success

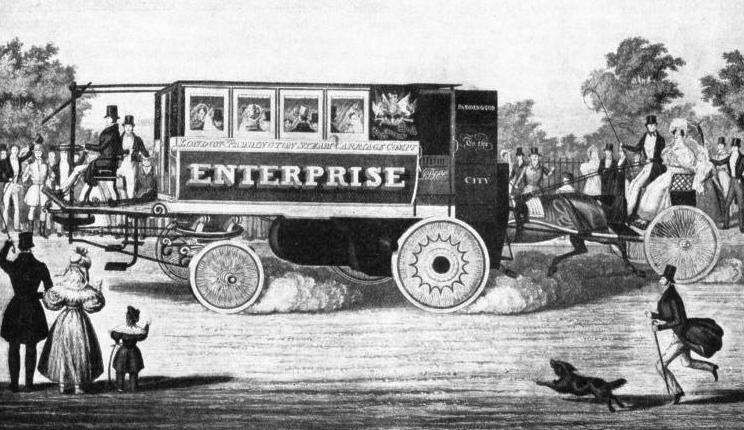

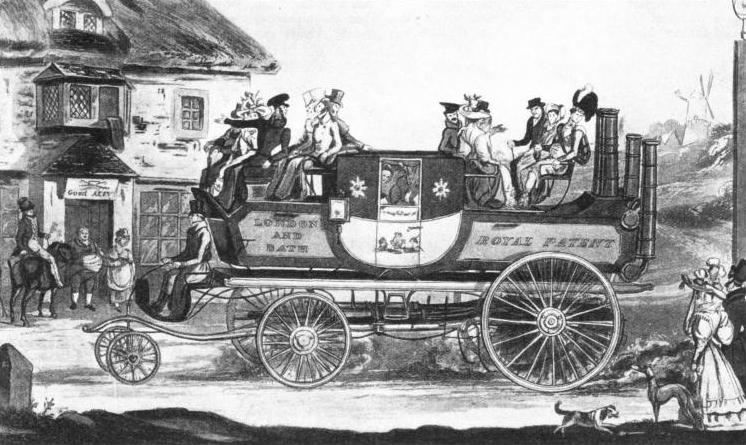

BUILT IN 1833 for the steam-

THE earliest attempts at producing a locomotive -

Land transport in its widest, most general sense was carried out entirely on the turnpike roads, and the first attempts to mechanize it were expressed not in steam trains, but in steam coaches. Before and during the eighteen-

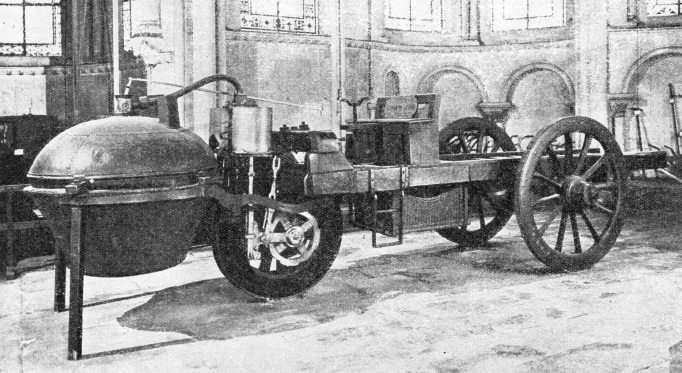

The first engineer in the world to produce a workable locomotive was the Frenchman Nicolas Cugnot. His invention took the form of a steam traction engine, mounted on ironshod wheels. He aimed at building an appliance which could haul heavy artillery. For such an engine any ambitious Government might be prepared to pay highly. Cugnot’s traction engine appears a crude and curious machine to-

Cugnot’s first experimental engine, or steam carriage, appeared in 1769. It ran on three wheels -

Encouraged by this first attempt, the ingenious Frenchman designed another and larger steam carriage, exemplifying the same principles of design as before. The French Government assisted him and in 1770 he produced a steam carriage which, with several passengers, travelled along a public street at a slow walking pace. The driving wheel, with the entire engine and boiler that it supported, was mounted on a pivot, by which Cugnot steered his machine. He did not find steering easy, and had not gone far before his carriage refused to answer the helm and charged a wall. At this, people became nervous, and Cugnot was admonished severely by the authorities. He did not despair, though the French Government became noticeably cooler. But the faulty steering gear was to give trouble again. Cugnot’s steam carriage was unstable and its instability was aggravated by the fact that all the heavy machinery rested on the single wheel in front. As soon as he attempted to drive it round a street corner, it heeled over and fell on its side. The authorities thereupon confiscated the carriage and imprisoned the unfortunate father of modern locomotion. The original 1770 machine is still to be seen at the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers, Paris.

In 1788 a Yorkshireman named Robert Fourness designed a three-

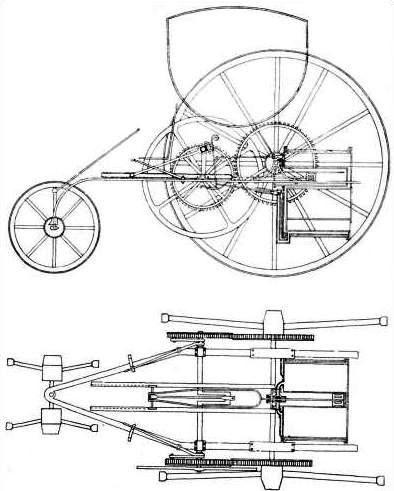

Richard Trevithick is rightly claimed as the father of the railway engine. He built the first locomotive to run on rails and set it to work on the Penydarran tramroad in South Wales in 1801. But several years before that he had been experimenting with steam carriages for use on roads. As the eighteenth merged into the nineteenth century, Trevithick was experimenting with a model steam traction engine. It had a horizontal boiler mounted on three wheels, of which the larger two were the driving wheels. The single cylinder drove on to a crankshaft with a huge flywheel, whence gear wheels transmitted the motion to the driving axle. The inventor received little encouragement.

Trevithick, however, found an able partner in young Andrew Vivian, and these two set to work to produce a real road coach, one that could travel along the highways and carry passengers. Working at Redruth, in Cornwall, where Trevithick lived, they produced an enlarged version of Trevithick’s pioneer effort, and mounted a small carriage body over the engine and between the two huge driving wheels. One day in 1801 this prodigy steamed out of the Cornish town of Camborne in the small hours of the morning, with Trevithick and Vivian on board. The first person they met was the keeper at the toll gate, who took one look at the panting monster, muttered something about the Devil and there being no charge, and hurriedly disappeared into the toll house. Trevithick and Vivian drove their carriage, under its own steam, from Camborne to Plymouth, covering some seventy miles of rough Cornish roads. At Plymouth it was placed on board ship and conveyed to London. The carriage excited great wonder but no profitable enthusiasm for steam carriages on roads. At the same time it gained for Trevithick the reputation through which he was commissioned to build the first railway locomotive.

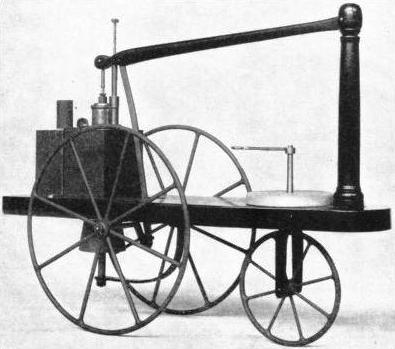

Trevithick was not, however, the first man in England to make a steam engine run along under its own power. William Murdock, the pioneer of gas lighting, who was responsible for the working of Boulton and Watt’s mining engines in Cornwall, built a simple little three-

Engine at the Back

Murdock set off for London with his model, but unfortunately met Boulton on the way at Exeter. Boulton afterwards wrote to James Watt: “He hath unpacked his carriage and made it travel a mile . . . making it carry the fire shovel, poker and tongs. I think it fortunate that I met him, as I am persuaded I can cure hint of the disorder, or turn the evil to good.” That was in September 1786.

Many years later, when the building of railway locomotives had been begun, certain engineers were experimenting with a remarkable alternative, in the form of high-

DRAWINGS OF TREVITHICK’S STEAM COACH furnished with his patent specification in 1802. The drawings represent a coach built in the previous year. Trevithick and his partner, Andrew Vivian, drove the coach from Camborne, Cornwall, to Plymouth.

Several names stand out among those of early nineteenth-

Gurney placed his engine at the back. He had various reasons for this. First, the trailing axle, being the driving axle, gave a maximum possible weight for adhesion. Secondly, the fumes from the boiler flues were in no way likely to annoy the passengers. Thirdly, as the coach body screened the engine, it was less likely to frighten horses on the road, an important consideration in days when there were thousands of high-

There were disadvantages in the rearward position for the engine. Foremost among these was that the driver, who sat guiding the coach in front, could not keep an eye on the engine. The engine proper was below the level of the coachwork, with its driving shaft geared to the axle.

In addition, Gurney provided a series of “struts” for giving assistance when climbing steep hills. These “struts” were legs to which motion was imparted through connecting rods, and which dug into the road surface underneath. They hindered rather than assisted the coach, and the inventor removed them. The coach climbed hills more easily with the unassisted aid of its driving wheels. For a steam generator, Gurney used an ingenious water tube boiler, burning coke. This boiler was a quick steamer, remarkably so when we recall the cumbersome boilers used on contemporary railway engines and the lack of experience which engineers displayed in boiler-

A Long-

The whole coach was a beautiful piece of work, with graceful lines, which were well set off by the yellow and black colour scheme. Gurney tested the coach on the London-

These brave beginnings attracted a great deal of attention, favourable and otherwise. Far-

CUGNOT’S STEAM TRACTION ENGINE OF 1770 was built tor hauling heavy artillery. The two-

Walter Hancock, a contemporary of Gurney, was also much interested in steam coach design. He began his first experiments in 1824, but did not succeed in conveying fare-

Hancock’s steam generator consisted of a light cellular boiler. For materials he used copper and gunmetal. The boiler was a marvel of compactness combined with good steaming qualities, so much so that modern motor engineers can claim merely to have revived lightweight propulsion, not to have introduced it. Some of the Hancock coaches were most efficient. His curiously named Infant first ran from London to Brighton on November 1, 1832. Unfortunately, it ran short of coke on the way and took a long time to reach its destination. On the return the average speed, including stops for coke and water, was as much as six miles an hour. In 1832 Hancock inaugurated the first regular urban motor bus service. His steam omnibus Enterprise was built for this service in 1833. It ran in London between Paddington (which had no railway station in those days) and the Bank. Between 1833 and 1836, when railways first reached London, Hancock carried more than 12,000 passengers on his Paddington-

Working Pressure of 150 lb

In 1833 Hancock put another steam coach on the road. This coach, which had the rather gruesome name of Autopsy, ran between London and Brighton, making the journey in five and a half hours and attaining a maximum speed of thirteen miles an hour. That was faster than the maximum speed allowed for motor buses within comparatively recent years. Hancock’s calculations showed that the owner of steam coaches could make a profit of 25 percent over all running expenses. This showing, which should have stimulated wealthy coach proprietors, unfortunately alarmed other influential persons, who would stop at nothing to prevent the spread of mechanical transport.

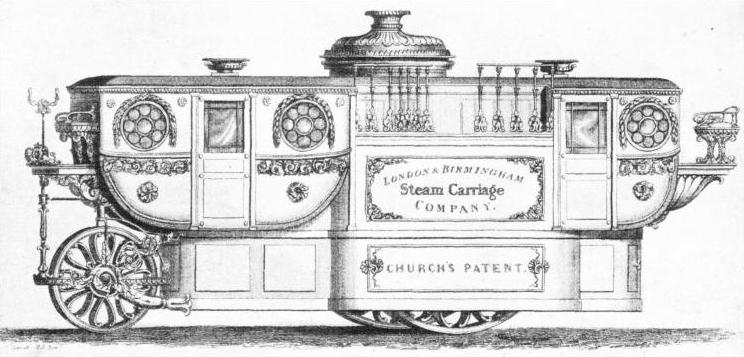

But in spite of threatening movements, engineers were busy on steam coaches at the beginning of the eighteen-

Steam coach wheels were normally of wood, with iron tyres, and resembled those of the ordinary stage coaches, except that they were rather stouter. There is no evidence that they damaged the roads in normal conditions and probably, as the Select Committee had claimed, the pounding of horses' hoofs on the macadam surface was far rougher.

Encouraged by initial success, Church designed a coach larger than any hitherto proposed, on the same lines as his existing three-

COPY OF MURDOCK’S EXPERIMENTAL MODEL, which the inventor produced in 1782-

The trouble, with early steam coach proprietors was that they saw in their vehicles a substitute for horse transport and for railway transport. Had they tried to introduce steam road coaches as feeders to the new railways in districts where branch lines would have, been unremunerative, there is little doubt but that the rich and influential railway companies would have given them all the backing they deserved, and enabled steam coaching to prevail against its more reactionary enemies. Only to-

Remarkable steam coaching developments took place in Scotland about 1830. James Nasmyth, whose name has gone down to history in other branches of engineering, was early on the scene with a steam car which he operated between Edinburgh and the Queen’s Ferry (Dalmeny) for the carriage of anyone bold enough to take a trip. Nasmyth’s car was not an outstanding vehicle. For propulsion, he installed a vertical engine and boiler at the back, the pistons imparting their motion through overhead crossheads. The arrangement somewhat resembled that of the historic railway locomotive Novelty of 1829, which was matched against Stephenson’s Rocket. Nasmyth was evidently not struck with his own invention, for after a while he scrapped the coach and sold the engine for stationary duties.

But Scotland saw one of the most remarkable developments of all in the work of John Scott Russell. Nasmyth’s steam car had been a simple experiment; Russell set out to produce an efficient means of urban or interurban road transport, and in this, for the time, he succeeded. Russell took the stage coach as his model, reinforcing its undercarriage and springing to support the heavier weight of the machinery. The springing alone showed that Russell had remarkable knowledge of the dynamics of a more or less heavy vehicle passing over an uneven road surface. As Gurney had done, Russell placed his machinery behind the coach body, in the place of what would be the after boot of an ordinary coach. For a motor he installed a two-

Miracle of Compactness

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Russell’s design was the gearing of the driving axle. To allow for the variation in revolution speed of the two driving wheels when rounding corners, Russell fitted two clutches whereby either wheel could be thrown out of gear. His carriage was thus able to turn sharply without skidding or damaging the road surface. In this he anticipated by many years the differential of modern motoring practice.

Russell fitted a steam generator which was a miracle of compactness, and which attained a remarkably high degree of thermal efficiency. His boiler was rectangular in shape and built up of copper plates. The firebox and smoke-

THE FIRST STEAM COACH, resembling a steam-

Against shocks from inequalities in the road surface, Russell mounted his machinery on a set of S-

The local authorities, however, watched Russell’s success with an unfriendly eye. Their workmen were instructed to spread a thick layer of loose stones over the surfaces of the roads along which the coaches passed. All that happened was that the existing horse-

How far the ingenious Russell might have gone we shall never know, for a sad accident overtook his enterprise. Probably the overcrowding of the coaches was responsible for the accident. Whatever it was, one of the coaches was upset through the breakage of a wheel. The vehicle heeled over, and the bottom plates of the boiler came into violent contact with the ground. The boiler immediately exploded, blowing much of the coach to fragments and causing heavy casualties among the passengers.

The authorities promptly ordered Russell’s remaining five coaches off their roads at once, and a splendid beginning was brought to an abrupt and untimely end. Two of the displaced coaches were brought to London, where such vehicles were still tolerated. They made occasional trips to Kew, Windsor and Greenwich. For a while, too, one of them plied between Hyde Park Corner and Hammersmith.

There were various reasons why these earliest motor services -

Speed Limit of 4 mph

The Turnpike Trust consisted of men intolerant of change. Many of them still did not believe in the ultimate success of railways, and they were determined not to allow steam engines on the public highroads. They could not forbid entirely the use of these steam engines, but they adopted the old plan of taxing them out of existence. Though it had been proved that a steam coach did no more, probably less, damage to the road than a coach and four, the Turnpike Trust had the price of a steam coach licence made twelve times that of a coach and four horses. The industry had been dead many years when the repressive Act of 1865 was passed. Under this Act every road locomotive had to be preceded at a distance of one hundred yards by a man on foot carrying a red flag to warn passengers of the locomotive’s approach. The speed limit was fixed at four miles an hour.

The development of heavy traction engines, it is true, was not unduly impeded by this Act. The large steam tractor gained rapidly in popularity from the eighteen-

A number of Mid-

It was not until the early years of the present century that road motor vehicles reappeared in any numbers on the roads of Great Britain. Had their predecessors been given a reasonable chance, there is little doubt that mechanical road transport and railways would have grown up side by side and many economic transport problems of to-

HEAVY ORNAMENTATION was one of the outstanding features of the steam carriages designed by William Church. In 1832 he inaugurated a service between London and Birmingham, but this was suspended when the railway was opened a few years later. Two types of vertical boiler were invented by Church to provide steam for his carriages, which were three-

You can read more on “Modern Traffic Control”, “Origin of the Steam Engine” and “The Work of Benz and Daimler” on this website.