© Wonders of World Engineering 2014-

Part 36

Part 36 of Wonders of World Engineering was published on Tuesday 2nd November 1937, price 7d.

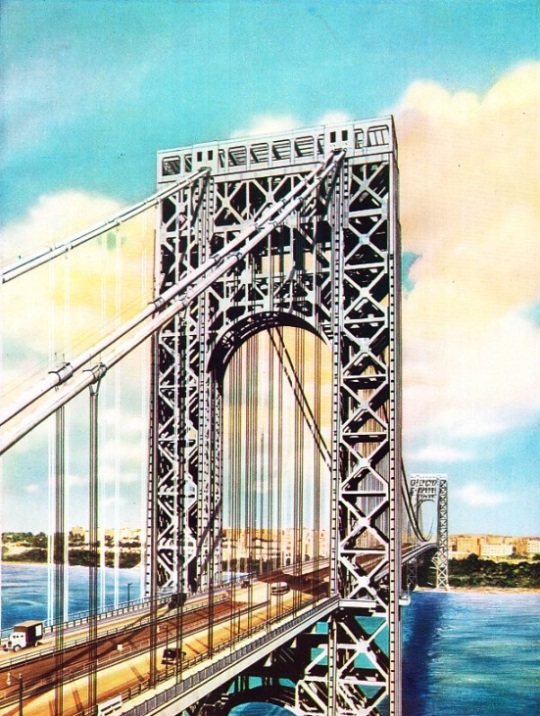

Part 36 includes a colour plate showing the George Washington Bridge. It formed part of the article on the George Washington Suspension Bridge.

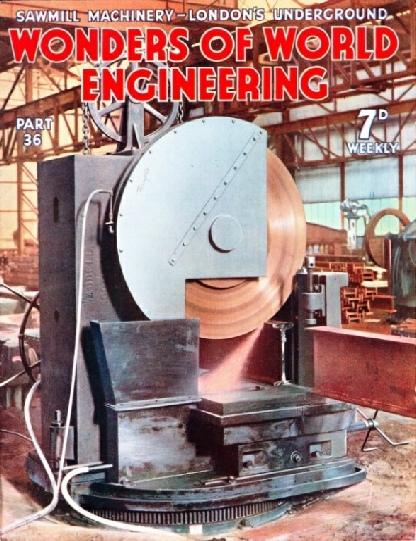

The Cover

This week’s cover shows a circular saw which has no teeth at all and which, moreover, cuts its way through steel much more rapidly than a toothed saw. This saw, in the Swansea works of Sir William Arrol & Co Ltd, is what is known as a friction saw. The steel disk spins round with a peripheral speed of 20,000 feet a minute. The resulting friction of the disk against the work is so great that the metal is burnt away, the saw being fed in as the cut is made. Friction saws are suitable only for work which is not thick, as, for instance, the joist shown in the illustration. For thicker work a toothed saw revolving comparatively slowly is used. The disk of a friction saw is sometimes made of abrasive material.

Contents of Part 36

Story of the Cinematograph - 2 (Part 2)

The story of the sound film and the later development of colour film. The chapter is concluded from part 35 and is the fourth article in the series Invention and Development.

The George Washington Bridge

Separating New York from New Jersey, the great Hudson River has long been an obstacle to transport. The opening of the great George Washington Suspension Bridge in 1932 completed an important new link in the highway systems of the two States. This chapter is the twelfth article in the series Linking the World’s Highways.

The George Washington Bridge (colour plate)

The George Washington Bridge

LINKING NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY, the George Washington Bridge across the Hudson River was opened for traffic in 1932. Each of the two towers is 559 ft 6 in high from the top of its pier to the summit of the steelwork. The two great piers have their centres 3,500 feet apart. The anchor span on the Manhattan side is 650 feet long, that on the New Jersey side is 610 feet long. The total length of the bridge, with its approach ramps, is 8,716 feet. The headway in the middle is 213 feet above the river. The two towers contain 41,000 tons of steel.

This colour plate previously appeared on the cover of part 11, to illustrate an article on New York’s Giant Bridges.